How Does Modernist Art and Literature Compare to Previous Generations

Franz Marc, 1913 "The Fate of the animals."

Modernism, here limited to aesthetic modernism (encounter also modernity), describes a series of sometimes radical movements in fine art, architecture, photography, music, literature, and the applied arts which emerged in the three decades before 1914. Modernism has philosophical antecedents that can be traced to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment but is rooted in the changes in Western society at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries.

Modernism encompasses the works of artists who rebelled against nineteenth-century academic and historicist traditions, believing that earlier aesthetic conventions were becoming outdated. Modernist movements, such as Cubism in the arts, Atonality in music, and Symbolism in poetry, directly and indirectly explored the new economic, social, and political aspects of an emerging fully industrialized world.

Modernist art reflected the deracinated experience of life in which tradition, community, commonage identity, and faith were eroding. In the twentieth century, the mechanized mass slaughter of the First World War was a watershed issue that fueled modernist distrust of reason and farther sundered complacent views of the steady moral improvement of human society and belief in progress.

Initially an avant guarde movement confined to an intellectual minority, modernism achieved mainstream acceptance and exerted a pervasive influence on civilisation and popular entertainment in the course of the twentieth century. The modernist view of truth as a subjective, frequently intuitive claim has contributed to the elevation of individualism and moral relativism as guiding personal ideals and contributed to far-reaching transformations regarding the spiritual significance of human life.

Philosophical and historical background

From the 1870s onward, the ideas that history and civilization were inherently progressive and that progress was always good came under increasing attack. Arguments arose that non merely were the values of the artist and those of order dissimilar, merely that society was antithetical to progress, and could not move forward in its present form. Philosophers chosen into question the previous optimism.

Two of the most disruptive thinkers of the period were, in biology, Charles Darwin and, in political science, Karl Marx. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural pick undermined religious certainty and the sense of homo uniqueness, which had far-reaching implications in the arts. The notion that homo beings were driven by the same impulses as "lower animals" proved to exist difficult to reconcile with the idea of an ennobling spirituality. Marx seemed to present a political version of the same suggestion: that bug with the economical order were non transient, the outcome of specific wrong doers or temporary conditions, just were fundamentally contradictions within the "capitalist" system. Naturalism in the visual arts and literature reflected a largely materialist notion of human life and society.

Separately, in the arts and messages, 2 ideas originating in France would accept particular impact. The first was Impressionism, a school of painting that initially focused on work done, not in studios, only outdoors (en plein air). Impressionist paintings demonstrated that human beings do non see objects, but instead meet light, itself. The 2d schoolhouse was Symbolism, marked by a belief that linguistic communication is expressly symbolic in its nature, and that verse and writing should follow connections that the sheer sound and texture of the words create.

At the same time, social, political, religious, and economical forces were at piece of work that would become the basis to contend for a radically different kind of art and thinking. In religion, biblical scholars argued that that the biblical writers were not conveying God's literal word, but were strongly influenced by their times, societies, and audiences. Historians and archaeologists further challenged the factual basis of the Bible and differentiated an evidence-based perspective of the past with the worldview of the ancients, including the biblical authors, who uncritically accepted oral and mythological traditions.

Main amid the physical influences on the development of modernism was steam-powered industrialization, which produced buildings that combined art and engineering, and in new industrial materials such as cast iron to produce bridges and skyscrapers—or the Eiffel Belfry, which broke all previous limitations on how tall man-made objects could exist—resulting in a radically different urban environment.

The possibilities created by scientific test of subjects, together with the miseries of industrial urban life, brought changes that would milkshake a European civilization, which had previously regarded itself every bit having a continuous and progressive line of evolution from the Renaissance. With the telegraph offering instantaneous communication at a distance, the experience of time itself was altered.

The breadth of the changes tin can be sensed in how many modern disciplines are described every bit existence "classical" in their pre-twentieth-century form, including physics, economic science, and arts such as ballet, theater, or architecture.

The first of Modernism: 1890-1910

Self-portrait of Edouard Manet

The roots of Modernism emerged in the center of the nineteenth century; and rather locally, in France, with Charles Baudelaire in literature and Édouard Manet in painting, and perhaps with Gustave Flaubert, too, in prose fiction. (It was a while afterward, and not so locally, that Modernism appeared in music and compages). The "advanced" was what Modernism was chosen at starting time, and the term remained to describe movements which identify themselves as attempting to overthrow some aspect of tradition or the status quo.

In the 1890s, a strand of thinking began to assert that it was necessary to push aside previous norms entirely, instead of merely revising past knowledge in light of current techniques. The growing motility in art paralleled such developments as Einstein's Theory of Relativity in physics; the increasing integration of the internal combustion engine and industrialization; and the increased office of the social sciences in public policy. It was argued that, if the nature of reality itself was in question, and if restrictions which had been in place effectually man activeness were falling, and so art, too, would have to radically alter. Thus, in the offset 15 years of the twentieth century a series of writers, thinkers, and artists fabricated the pause with traditional means of organizing literature, painting, and music.

Sigmund Freud offered a view of subjective states involving an unconscious mind total of fundamental impulses and counterbalancing self-imposed restrictions, a view that Carl Jung would combine with a belief in natural essence to stipulate a collective unconscious that was full of basic typologies that the conscious mind fought or embraced. Jung's view suggested that people's impulses towards breaking social norms were non the production of childishness or ignorance, but were instead essential to the nature of the human animal, the ideas of Darwin having already introduced the concept of "human being, the animal" to the public mind.

Friedrich Nietzsche championed a philosophy in which forces, specifically the 'Will to ability', were more important than facts or things. Similarly, the writings of Henri Bergson championed the vital "life forcefulness" over static conceptions of reality. What united all these writers was a romantic distrust of the Victorian positivism and certainty. Instead they championed, or, in the case of Freud, attempted to explain, irrational thought processes through the lens of rationality and holism. This was connected with the century-long trend to thinking in terms of holistic ideas, which would include an increased interest in the occult, and "the vital forcefulness."

Composer Arnold Schoenberg

Out of this collision of ideals derived from Romanticism, and an attempt to notice a way for noesis to explain that which was every bit nevertheless unknown, came the first moving ridge of works, which, while their authors considered them extensions of existing trends in art, bankrupt the implicit contract that artists were the interpreters and representatives of bourgeois culture and ideas. These "modernist" landmarks include Arnold Schoenberg's atonal ending to his 2nd Cord Quartet in 1908; the Abstract-Expressionist paintings of Wassily Kandinsky starting in 1903 and culminating with the founding of the Blue Rider group in Munich; and the rise of Cubism from the work of Picasso and Georges Braque in 1908.

Powerfully influential in this wave of modernity were the theories of Freud, who argued that the mind had a basic and key structure, and that subjective experience was based on the interplay of the parts of the listen. All subjective reality was based, according to Freud's ideas, on the play of bones drives and instincts, through which the outside world was perceived. This represented a break with the past, in that previously information technology was believed that external and absolute reality could impress itself on an individual, as, for example, in John Locke's tabula rasa doctrine.

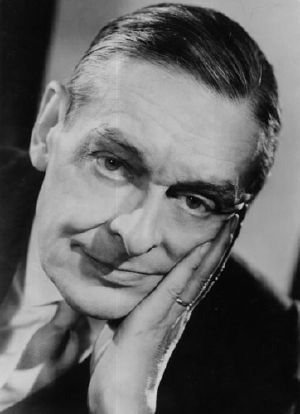

This wave of the Modern Movement broke with the past in the first decade of the twentieth century, and tried to redefine various art forms in a radical fashion. Leading lights within the literary wing of this trend included Basil Bunting, Jean Cocteau, Joseph Conrad, T. S. Eliot, William Faulkner, Max Jacob, James Joyce, Franz Kafka, D. H. Lawrence, Federico García Lorca, Marianne Moore, Ezra Pound, Marcel Proust, Gertrude Stein, Wallace Stevens, Virginia Woolf, and W. B. Yeats amongst others.

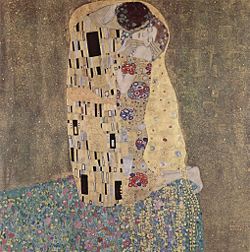

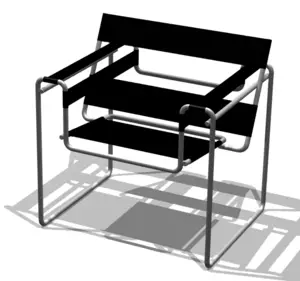

Composers such as Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and George Antheil represent Modernism in music. Artists such as Gustav Klimt, Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, and the movements Les Fauves, Cubism and the Surrealists represent various strains of Modernism in the visual arts, while architects and designers such as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe brought modernist ideas into everyday urban life. Several figures outside of artistic Modernism were influenced by artistic ideas; for example, John Maynard Keynes was friends with Woolf and other writers of the Bloomsbury group.

The explosion of Modernism: 1910-1930

On the eve of Globe War I a growing tension and unease with the social guild, seen in the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the agitation of "radical" parties, as well manifested itself in creative works in every medium which radically simplified or rejected previous practice. In 1913, famed Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, working for Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, equanimous Rite of Spring for a ballet, choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky that depicted man cede, and young painters such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were causing a shock with their rejection of traditional perspective as the ways of structuring paintings—a pace that none of the Impressionists, not even Cézanne, had taken.

These developments began to give a new pregnant to what was termed 'Modernism'. Information technology embraced disruption, rejecting or moving beyond simple Realism in literature and art, and rejecting or dramatically altering tonality in music. This set Modernists apart from nineteenth-century artists, who had tended to believe in "progress." Writers like Dickens and Tolstoy, painters similar Turner, and musicians similar Brahms were not 'radicals' or 'Bohemians', simply were instead valued members of society who produced art that added to society, even if it was, at times, critiquing less desirable aspects of it. Modernism, while it was nevertheless "progressive" increasingly saw traditional forms and traditional social arrangements as hindering progress, and therefore the artist was recast as a revolutionary, overthrowing rather than enlightening.

Futurism exemplifies this tendency. In 1909, F.T. Marinetti'south beginning manifesto was published in the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro; presently afterward a group of painters (Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini) co-signed the Futurist Manifesto. Modeled on the famous "Communist Manifesto" of the previous century, such manifestos put forward ideas that were meant to provoke and to gather followers. Strongly influenced past Bergson and Nietzsche, Futurism was function of the general trend of Modernist rationalization of disruption.

The Kiss, past Gustav Klimt

Modernist philosophy and art were all the same viewed as being only a part of the larger social movement. Artists such equally Klimt and Cézanne, and composers such equally Mahler and Richard Strauss were "the terrible moderns"—other radical avant-garde artists were more heard of than heard. Polemics in favor of geometric or purely abstract painting were largely confined to 'little magazines' (like The New Age in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland) with tiny circulations. Modernist primitivism and pessimism were controversial but were non seen equally representative of the Edwardian mainstream, which was more inclined towards a Victorian organized religion in progress and liberal optimism.

However, World War I and its subsequent events were the cataclysmic upheavals that late nineteenth-century artists such as Brahms had worried most, and avant-gardists had anticipated. Kickoff, the failure of the previous status quo seemed cocky-axiomatic to a generation that had seen millions die fighting over scraps of earth—prior to the war, it had been argued that no ane would fight such a state of war, since the toll was as well loftier. 2d, the nascence of a machine age changed the conditions of life—machine warfare became a touchstone of the ultimate reality. Finally, the immensely traumatic nature of the experience dashed basic assumptions: Realism seemed to be bankrupt when faced with the fundamentally fantastic nature of trench warfare, as exemplified by books such as Erich Maria Remarque'southward All Quiet on the Western Front. Moreover, the view that mankind was making tedious and steady moral progress came to seem ridiculous in the confront of the senseless slaughter of the Great War. The First World War at once fused the harshly mechanical geometric rationality of technology with the nightmarish irrationality of myth.

Thus in the 1920s, Modernism, which had been a minority taste before the war, came to define the age. Modernism was seen in Europe in such critical movements as Dada, and and then in constructive movements such every bit Surrealism, as well as in smaller movements of the Bloomsbury Group. Each of these "modernisms," every bit some observers labeled them at the time, stressed new methods to produce new results. Again, Impressionism was a precursor: breaking with the idea of national schools, artists and writers and adopting ideas of international movements. Surrealism, Cubism, Bauhaus, and Leninism are all examples of movements that chop-chop found adherents far beyond their original geographic base.

Illustration of the Spirit of St. Louis

Exhibitions, theater, movie theater, books, and buildings all served to cement in the public view the perception that the world was changing. Hostile reaction often followed, equally paintings were spat upon, riots organized at the opening of works, and political figures denounced modernism as unwholesome and immoral. At the same fourth dimension, the 1920s were known equally the "Jazz Age," and the public showed considerable enthusiasm for cars, air travel, the telephone, and other technological advances.

By 1930, Modernism had won a identify in the establishment, including the political and artistic establishment, although by this time Modernism itself had changed. In that location was a general reaction in the 1920s against the pre-1918 Modernism, which emphasized its continuity with a by while rebelling against it, and against the aspects of that period which seemed excessively mannered, irrational, and emotional. The post-World-War period, at first, veered either to systematization or nihilism and had, as perhaps its nearly paradigmatic movement, Dada.

While some writers attacked the madness of the new Modernism, others described it as soulless and mechanistic. Among Modernists at that place were disputes about the importance of the public, the relationship of fine art to audience, and the role of fine art in lodge. Modernism comprised a series of sometimes-contradictory responses to the situation as it was understood, and the try to wrestle universal principles from it. In the end science and scientific rationality, oft taking models from the eighteenth century Enlightenment, came to be seen as the source of logic and stability, while the basic archaic sexual and unconscious drives, along with the seemingly counter-intuitive workings of the new machine age, were taken as the basic emotional substance. From these two poles, no thing how seemingly incompatible, Modernists began to mode a complete worldview that could encompass every aspect of life, and express "everything from a scream to a chuckle."

Modernism's second generation: 1930-1945

By 1930, Modernism had entered popular civilisation. With the increasing urbanization of populations, it was get-go to be looked to as the source for ideas to deal with the challenges of the day. As Modernism gained traction in academia, it was developing a self-conscious theory of its own importance. Popular culture, which was not derived from high culture but instead from its ain realities (especially mass product), fueled much Modernist innovation. Modernistic ideas in fine art appeared in commercials and logos, the famous London Underground logo being an early example of the need for clear, easily recognizable and memorable visual symbols.

Another strong influence at this time was Marxism. After the by and large primitivistic/irrationalist attribute of pre-World-War-One Modernism, which for many Modernists precluded any attachment to merely political solutions, and the Neo-Classicism of the 1920s, as represented most famously by T. Due south. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky—which rejected pop solutions to modern issues—the rising of Fascism, the Great Depression, and the march to war helped to radicalize a generation. The Russian Revolution was the catalyst to fuse political radicalism and utopianism with more expressly political stances. Bertolt Brecht, Due west. H. Auden, Andre Breton, Louis Aragon, and the philosophers Gramsci and Walter Benjamin are mayhap the most famous exemplars of this Modernist Marxism. This move to the radical left, still, was neither universal nor definitional, and there is no item reason to associate Modernism, fundamentally, with 'the left'. Modernists explicitly of "the right" include Wyndham Lewis, William Butler Yeats, T. Due south. Eliot, Ezra Pound, the Dutch author Menno ter Braak, and many others.

One of the near visible changes of this period is the adoption of objects of modernistic production into daily life. Electricity, the telephone, the machine—and the need to work with them, repair them, and live with them—created the need for new forms of manners, and social life. The kind of confusing moment which only a few knew in the 1880s became a common occurrence as telecommunications became increasingly ubiquitous. The speed of communication reserved for the stockbrokers of 1890 became role of family life.

Modernism in social organization would produce inquiries into sex and the basic bondings of the nuclear, rather than extended, family. The Freudian tensions of infantile sexuality and the raising of children became more than intense, because people had fewer children, and therefore a more specific relationship with each kid: the theoretical, once more, became the practical and even popular. In the arts every bit well as pop civilization sexuality lost its mooring to marriage and family and increasingly came to be regarded as a self-oriented biological imperative. Explicit depictions of sexual practice in literature, theater, picture show, and other visual arts often denigrated traditional or religious conceptions of sex and the implicit relationship between sex activity and procreation.

Modernism's goals

The 'Glass Palace' (1935) in the Netherlands - functional and open up

Many modernists believed that by rejecting tradition they could discover radically new ways of making art. Arnold Schoenberg believed that past rejecting traditional tonal harmony, the hierarchical system of organizing works of music which had guided music-making for at to the lowest degree a century and a half, and perhaps longer, he had discovered a wholly new way of organizing sound, based on the use of 12-note rows. This led to what is known as serial music by the post-war period.

Abstract artists, taking every bit their examples from the Impressionists, as well as Paul Cézanne and Edvard Munch, began with the assumption that colour and shape formed the essential characteristics of art, not the depiction of the natural world. Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich all believed in redefining art as the organization of pure color. The use of photography, which had rendered much of the representational role of visual art obsolete, strongly affected this attribute of Modernism. However, these artists also believed that by rejecting the depiction of material objects they helped art move from a materialist to a spiritualist phase of evolution.

Other Modernists, particularly those involved in design, had more pragmatic views. Modernist architects and designers believed that new applied science rendered old styles of building obsolete. Le Corbusier idea that buildings should office as "machines for living in," analogous to cars, which he saw every bit machines for traveling in. Simply as cars had replaced the horse, so Modernist design should turn down the former styles and structures inherited from Aboriginal Greece or from the Eye Ages. Following this auto aesthetic, Modernist designers typically reject decorative motifs in design, preferring to emphasize the materials used and pure geometrical forms. The skyscraper, such equally Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building in New York (1956–1958), became the archetypal Modernist edifice.

Modernist design of houses and piece of furniture also typically emphasized simplicity and clarity of course, open-plan interiors, and the absence of ataxia. Modernism reversed the nineteenth-century relationship of public and private: in the nineteenth century, public buildings were horizontally expansive for a variety of technical reasons, and private buildings emphasized verticality—to fit more private space on more than and more limited land.

In other arts, such pragmatic considerations were less important. In literature and visual art, some Modernists sought to defy expectations mainly in order to brand their art more vivid, or to force the audience to take the trouble to question their own preconceptions. This attribute of Modernism has often seemed a reaction to consumer civilization, which developed in Europe and North America in the late-nineteenth century. Whereas nigh manufacturers endeavor to make products that will be marketable past appealing to preferences and prejudices, High Modernists rejected such consumerist attitudes in order to undermine conventional thinking.

Many Modernists saw themselves as apolitical. Others, such equally T. S. Eliot, rejected mass pop culture from a bourgeois position. Indeed, i could contend that Modernism in literature and fine art functioned to sustain an elite civilization which excluded the majority of the population.

Modernism's reception and controversy

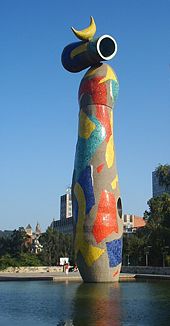

Ceramic Sculpture by Joan Miró

The nearly controversial attribute of the Mod move was, and remains, its rejection of tradition. Modernism's stress on liberty of expression, experimentation, radicalism, and primitivism disregards conventional expectations. In many art forms this often meant startling and alienating audiences with bizarre and unpredictable furnishings: the foreign and disturbing combinations of motifs in Surrealism, the use of extreme dissonance and atonality in Modernist music, and depictions of nonconventional sexuality in many media. In literature Modernism often involved the rejection of intelligible plots or label in novels, or the creation of poesy that defied clear estimation.

The Soviet Communist government rejected Modernism after the ascension of Stalin on the grounds of alleged elitism, although information technology had previously endorsed Futurism and Constructivism; and the Nazi government in Germany deemed it narcissistic and nonsensical, likewise as "Jewish" and "Negro." The Nazis exhibited Modernist paintings alongside works by the mentally ill in an exhibition entitled Degenerate fine art.

Modernism flourished mainly in consumer/backer societies, despite the fact that its proponents often rejected consumerism itself. Withal, High Modernism began to merge with consumer civilisation after World War Two, specially during the 1960s. In Britain, a youth sub-culture fifty-fifty chosen itself "moderns," though commonly shortened to Mods, following such representative music groups every bit The Who and The Kinks. Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, and Pink Floyd combined popular musical traditions with Modernist poetry, adopting literary devices derived from Eliot, Apollinaire, and others. The Beatles developed forth similar lines, creating various Modernist musical effects on several albums, while musicians such as Frank Zappa, Syd Barrett, and Helm Beefheart proved even more experimental. Modernist devices also started to appear in popular cinema, and later in music videos. Modernist design as well began to enter the mainstream of popular culture, as simplified and stylized forms became popular, often associated with dreams of a infinite historic period loftier-tech future.

This merging of consumer and high versions of Modernist culture led to a radical transformation of the meaning of "modernism." Firstly, it implied that a movement based on the rejection of tradition had become a tradition of its ain. Secondly, it demonstrated that the distinction between aristocracy Modernist and mass-consumerist civilization had lost its precision. Some writers declared that Modernism had become so institutionalized that information technology was now "mail avant-garde," indicating that it had lost its power as a revolutionary movement. Many take interpreted this transformation equally the outset of the stage that became known as Mail-Modernism. For others, such as, for example, art critic Robert Hughes, Post-Modernism represents an extension of Modernism.

"Anti-Modern" or "counter-Mod" movements seek to emphasize holism, connection, and spirituality as being remedies or antidotes to Modernism. Such movements see Modernism as reductionist, and therefore subject to the failure to meet systemic and emergent effects. Many Modernists came to this viewpoint; for case, Paul Hindemith in his late plow towards mysticism. Writers such as Paul H. Ray and Sherry Ruth Anderson, in The Cultural Creatives, Fredrick Turner in A Culture of Hope, and Lester Brown in Plan B, take articulated a critique of the basic idea of Modernism itself—that individual creative expression should accommodate to the realities of technology. Instead, they debate, individual creativity should make everyday life more than emotionally acceptable.

In some fields, the effects of Modernism accept remained stronger and more than persistent than in others. Visual fine art has made the most complete interruption with its past. Most major uppercase cities have museums devoted to 'Modern Art' as distinct from post-Renaissance art (circa 1400 to circa 1900). Examples include the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Center Pompidou in Paris. These galleries make no stardom between Modernist and Mail service-Modernist phases, seeing both equally developments within 'Modernistic Art.'

References

ISBN links back up NWE through referral fees

- Bradbury, Malcolm, and James McFarlane (eds.). Modernism: A Guide to European Literature 1890–1930. Penguin, 1978. ISBN 0140138323

- Hughes, Robert. The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Modify. Gardners Books, 1991. ISBN 0500275823

- Levenson, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Modernism. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 052149866X

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. Pioneers of Mod Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Yale University Printing, 2005. ISBN 0300105711

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Sources of Modern Compages and Design, Thames & Hudson, 1985. ISBN 0500200726

- Weston, Richard. Modernism. Phaidon Press, 2001. ISBN 0714840998

Credits

New Globe Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accord with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Artistic Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may exist used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers hither:

- Modernism history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Modernism"

Note: Some restrictions may use to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/modernism

0 Response to "How Does Modernist Art and Literature Compare to Previous Generations"

Post a Comment